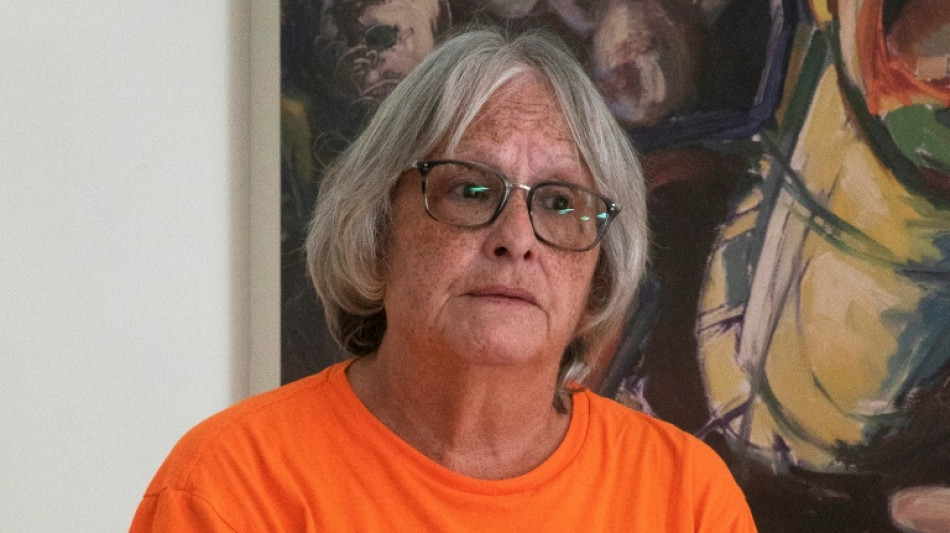

Roberta Hill, one of the thousands of Indigenous people who survived Canada's notorious Mohawk Institute residential school, said she was first sexually abused by an Anglican minister after bidding her visiting mother goodbye.

"I was so upset, so distraught, and I was crying," Hill, now 74, told AFP.

"I was taken into a room with the minister, and that's where the sexual abuse began... You're a little child. You don't know what the hell is going on," the retired nurse said.

Hill was back at the Mohawk Institute in the town of Brantford on Tuesday, the day it opened to the public as a museum documenting the horrors committed at the Ontario province school, which operated for roughly 140 years before its closure in 1970.

She was first brought to the school in 1957, along with five of her siblings, after their father died,and spent four years there before being sent into foster care.

Touring the site on Canada's National Day for Truth and Reconciliation, Hill entered what had been the room for family visits, where she had tearfully said goodbye to her mother before being victimized.

In the school basement, she peered into the furnace room, an area where boys were known to have been systematically abused.

She then walked into the nearby solitary confinement room -- a windowless closet with a wooden plank on the floor -- where, she recalled, her friend was held for two days after trying to run away.

"All I ever wanted to do was go home," Hill said.

- 'Mush hole' -

An estimated 150,000 First Nations, Inuit, and Metis children attended Canada's residential schools. They were abused and barred from speaking their languages -- part of a campaign that a government commission has called "cultural genocide."

The Mohawk Institute was Canada's oldest and longest-running residential school.

According to the Survivors' Secretariat, about 15,000 children attended the institute, which was widely known as the "mush hole" because the only food it served in its early years was mushy porridge three times a day.

Geronimo Henry, who was brought to the school in the 1940s, recalled how boys were ordered to fight each other.

"That was my home for 11 years," the 89-year-old told an audience assembled outside the imposing red-brick building with white porticos.

"I never went home for one day," he said. "I really did hard time."

- 'Lost' -

After the school closed in June 1970, there was debate about what to do with the building, with some calling for it to be torn down.

A campaign called "Save the Evidence" eventually raised more than $25 million ($18 million USD) to convert the site into a museum.

Sherri-Lyn Hill, chief of the Six Nations of the Grand River, said the building should serve as a place "for all to learn of a dark history, our shared history," stressing that the trauma suffered by school survivors continues to have "intergenerational impacts."

The retired nurse, Roberta Hill, explained that while she ultimately had a family and a three-decade career, the process of constructing a life after leaving the Mohawk Institute was arduous for her -- and proved impossible for others.

"You're lost," she said. "You know what it's like being in care here? Like somebody's controlling your every move."

She agreed with Chief Hill that the museum could foster broader awareness about the abusive residential school system, but stressed that effort should not fall only to survivors.

"I just want people to tell the truth. The church, the federal government," she said. "It shouldn't be just on us, because we didn't do this to ourselves."

W.Blondeel--LCdB